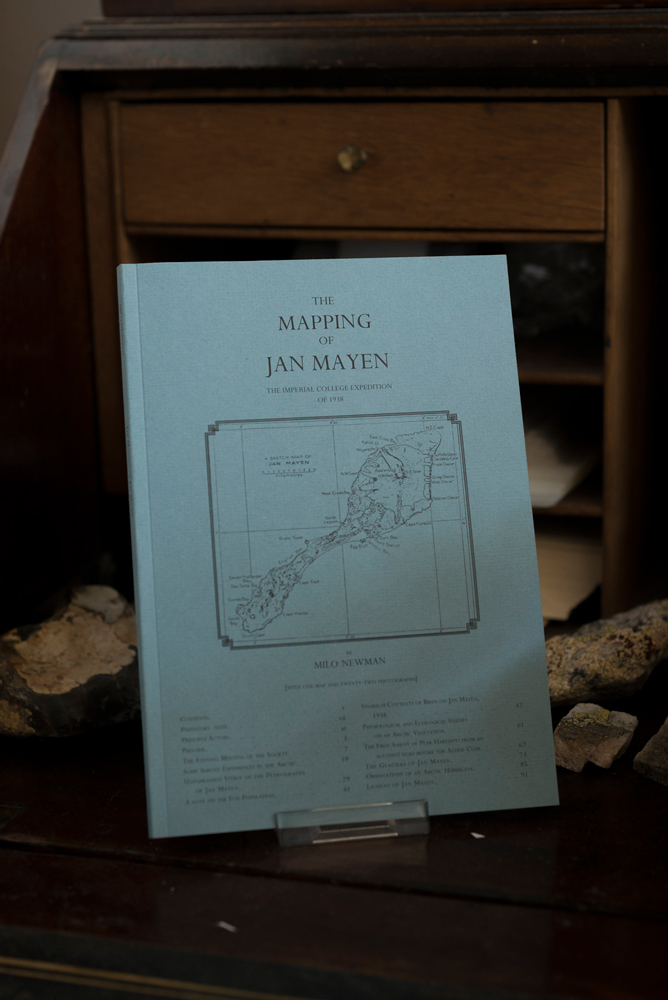

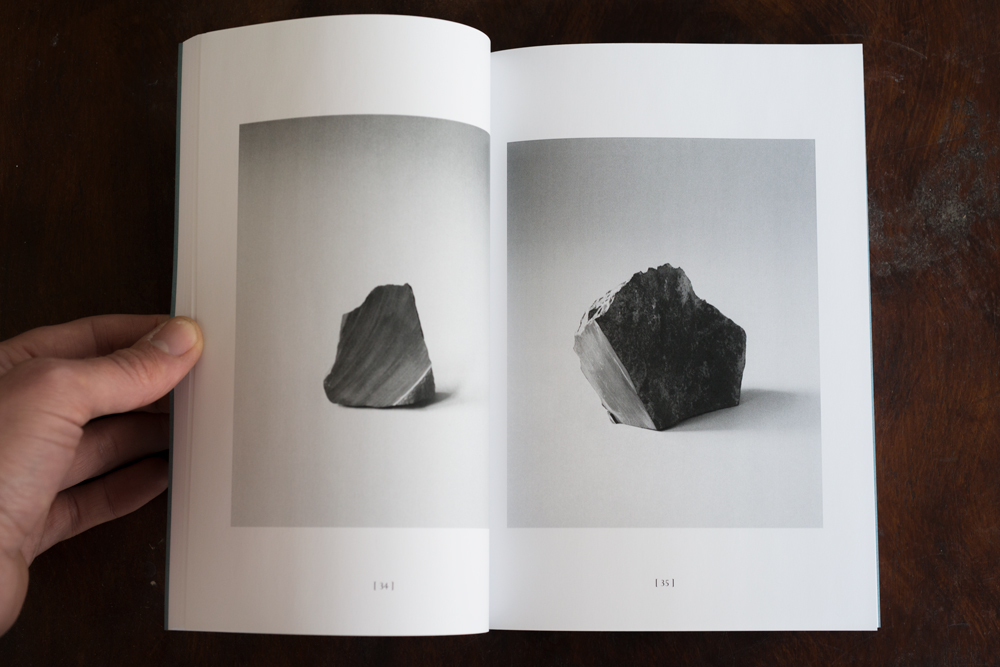

The Mapping of Jan Mayen is a bookwork that reinterprets an archive of scientific papers, maps, photographs and rock samples found by the artist amongst the collections of the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences during an EarthArt Fellowship. Interweaving episodes of memory, materiality, science, history and geography, the book tells—and ecologises—the story of a 1938 surveying expedition to the Arctic island of Jan Mayen made by Donald Ashby, a young geologist.

Between April and June 2019 three informal evening events were held based around the work. These included readings and a chance to explore an installation of the work in the geological collections storeroom.

Numbered and signed edition of 100 copies. 112pp, includes eleven written texts, twenty two photographs and one throwout map page. Copies available here for £15 plus postage.

Extract:

Along the northern coast of the centre of the island stands the Vogelberg, a jagged cliff formed from the collapsed remains of an ancient volcanic crater. Rising straight up from the sea, its enduring face appears charred, as if it had once been caught by a great fire, and is streaked with stratified tuff, compacted lava, and cinders. The world beneath this vertical flank is shadowed, and black seawater breaks against the rock. Mist catches on its highest peaks and drips downwards, filled with the screams of gulls and the chatter of seabirds.

The cliff itself is crammed with life; with raucous, disordered nests stacked vertiginously on top of each other amongst the unevenly eroded strata. Guillemot parents crowd the open and exposed ledges, pressed against the rock, their backs to the sea. Puffins squeeze themselves into the deeper horizontal crevices, their nests sparsely made of gull feathers. Fulmars turn their heads in unison, hollering at those who fly too close. On the lower reaches, eggs are balanced tentatively on overhanging and inward sloping protrusions of rock, which protect them from the water thrown up by breaking waves.

Many are lost. The lives of these birds are easily ruptured. Seen against the immense expanses of the northern ocean, their individual bodies are slight, and as breakable as eggshell. But their genealogies express something different; adapted through millions of years and multitudes of generations, they are an articulation of vibrant resilience. They embody this place, conveying a sense of how life might be lived in relation to the high, exposed sea-cliffs; the cold, fog-soaked air; and the dark realm of quick- silver fish beneath the surface of the open water.

Walking away from the base of the cliffs are King, Seligman, and several other members of the expedition. They are returning from a day spent observing the seabird colony and gathering data. As they walk, their curiosity takes hold, and they descend down to the old scientific station that lies in ruins in nearby Wilczekdalen. The buildings have a melancholy aspect, and have been mostly demolished by trappers searching for firewood. On the hillside a few yards away, the coffins of Norwegian hunters and an Austrian sailor stick dismally out of the ground, their graves marked with crosses.

The visitors find that the floor of the main hut is strewn with the carcasses of birds; in the fifty-five years since it was abandoned by the Austrian explorers it has become home to a lineage of arctic foxes, who for over thirteen successive generations have raised their cubs in the shelter of its cellar amongst the loosening boards and broken tables. From here, like thieves of acrobatic dexterity, they issue forth and undertake daring burglaries, ascending the nearby cliffs via impossible paths to steal the lives of the seabirds, their chicks and their eggs.

As the group of men carefully descend the ruined stairs into the basement, the youngest members of this vulpine ancestry peer back at them from across the disintegrating floor. Barely four months old, the young foxes are tame and inquisitive, and as they grow older they often follow the scientists around, playing and mouthing at each other. On one occasion, recalled by Russell, they approach quite closely, astonished and staring as he and Jennings remove their clothes and attempt to bathe in a frigid glacial tarn halfway up the Beerenberg on a spring-like day in late July.

The island known by the foxes cannot be truly mapped, though it is possible to imagine how it might exist for them; how it might appear not as an empty space simply awaiting this human drama, but as something very much alive in its absence. For theirs is an olfactory world, one that is touched with the nose, enriched by odours that shift and congeal, and whose area is traversed by cloud paths of scent that lend character to places and objects, and colour the memory.

During the war, whilst working for the Defence Science Policy Committee, King will be handed a letter intercepted from a Swiss pharmaceutical company, addressed to one of its subsidiaries. It contains details of a new insecticidal organochlorine called dichloro-diphenyl- trichloroethane. Immediately understanding its potential against the typhus, malaria and dengue fever carrying insects blighting the lives of Allied soldiers, he will organise its large-scale production and advocate its widespread use.

Years later, through a process of global distillation, the insidious toxic crystals of the chemical compound DDT will reach Jan Mayen. Its molecules will leech up through the food chain until they begin to accumulate, thinning the eggshells of the generations of seabirds which dwell on its cliffs, and gathering poisonously in the blood of the pale and light-footed foxes that prey on them.